Thanksgiving has come and gone, and Americans are already gearing up for their most cherished December holidays. However joyful the season is, though, there are some aspects that unfortunately will dampen the mood. Case in point: Bloomberg recently proclaimed, “Thanksgiving Meal Costs Most Ever as Bird Flu Hits Turkeys.” Apparently, our beloved American traditions are under threat from plagues and the rising cost of living.

But, as Marian Tupy of the Cato Institute points out, that’s “complete and utter nonsense.”

The Bloomberg article cited a figure from the American Farm Bureau Federation, which has dutifully recorded the prices of a basket of 12 essential goods, such as turkey, cranberries, and pumpkin pie mix, since 1986. According to the Farm Bureau, the price of a holiday dinner for 10 this year is $50.11, up 70 cents from 2014. The change is even more dramatic over the long term: a holiday dinner in 1986 cost just $28.74.

These figures may appear to be rising, but instead mostly reflect the change in nominal value on paper. As a result of inflation, the value of the dollar has declined over the same period. When we adjust to 2014 dollars for inflation, we find that the prices have gone down over time, from a high of $62.08 in 1986 to $49.41 in 2014.

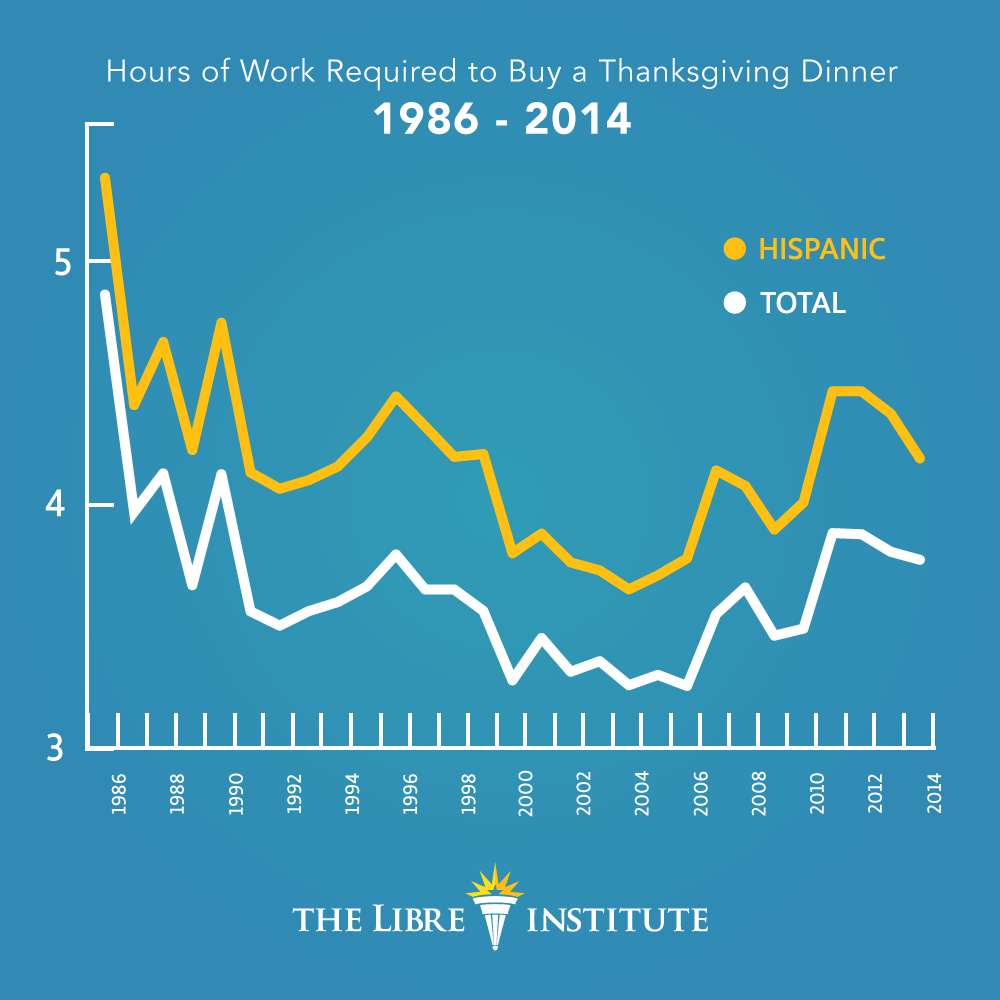

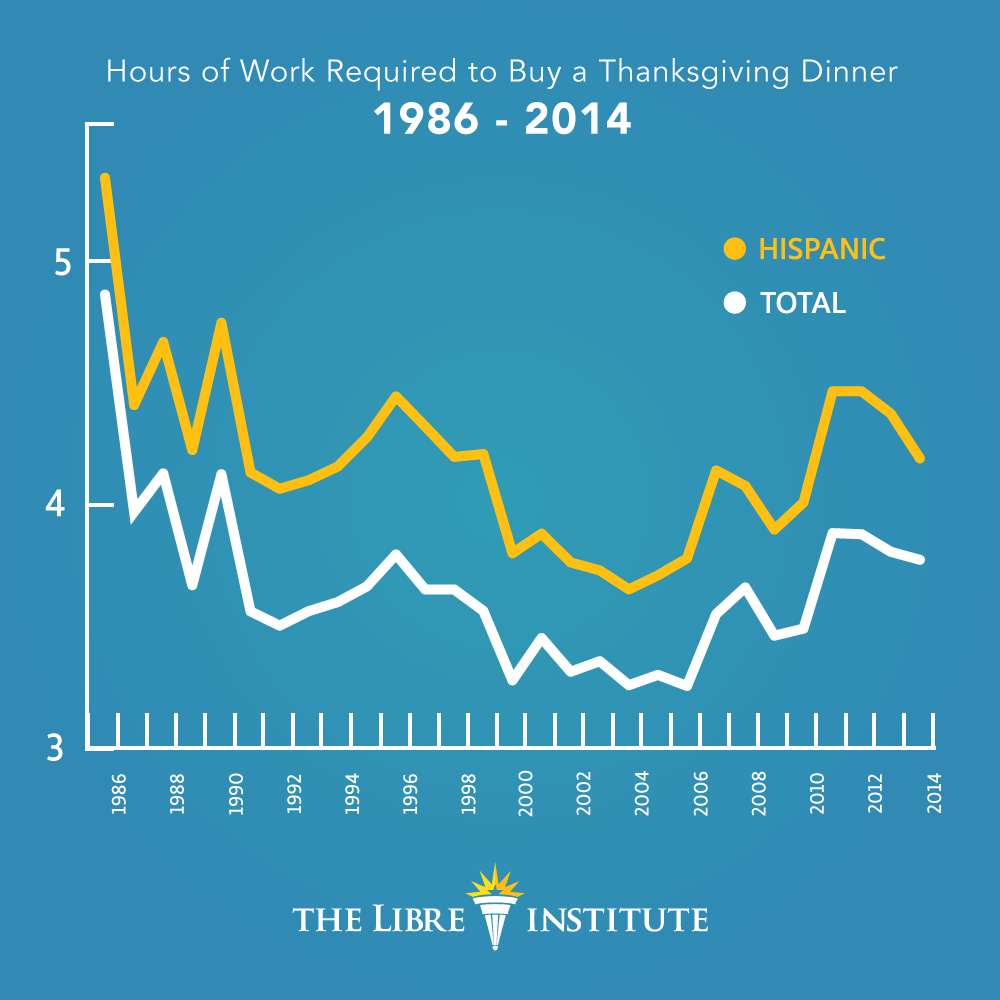

However, adjusting for inflation is only part of the task of discovering the true cost of goods and services. The productivity of workers changes over time, and an item or service that cost 5 hours of work one year might cost only 4 the next. Holiday dinners are no different, and when we factor in the change in average hourly wages using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, we arrive at a more human perspective on inflation, prices, and the value of our labor.

These days, a holiday dinner for 10 costs just over 4 hours of work for the median Hispanic earner, which is 22% less than it did 28 years ago. This is good news, and represents a significant decrease in the amount of time that has to be spent at the office or on the job – and more time with friends and family for the holidays — for Hispanic workers across America. While the median worker out of the total population only has to work 3 hours and 45 minutes for the same meal, that gap has been narrowing since 2011, and that is a positive sign. The disparity results from the fact that median hourly earnings are lower for Hispanics than for the national average, which highlights just how strong an impact the direction of the economy can have on quality of life.

Time is money, as the saying goes, and for no one in America is that claim truer than for hourly wage workers. Hispanic Americans continue to have to work longer hours to afford the same goods as the rest of the country does, but the gap has been narrowing recently. On the whole, even though the trend in cost of living has had its ups and downs, conditions historically have improved for Americans over time, which is a testament to the power of innovation in a free-market economy. This past Thanksgiving, Hispanic Americans spent only four fifths as much time working to put dinner on the table for their friends and family as they did 28 years ago. Despite what the prices on paper may say, that is real progress and something for which to be thankful.