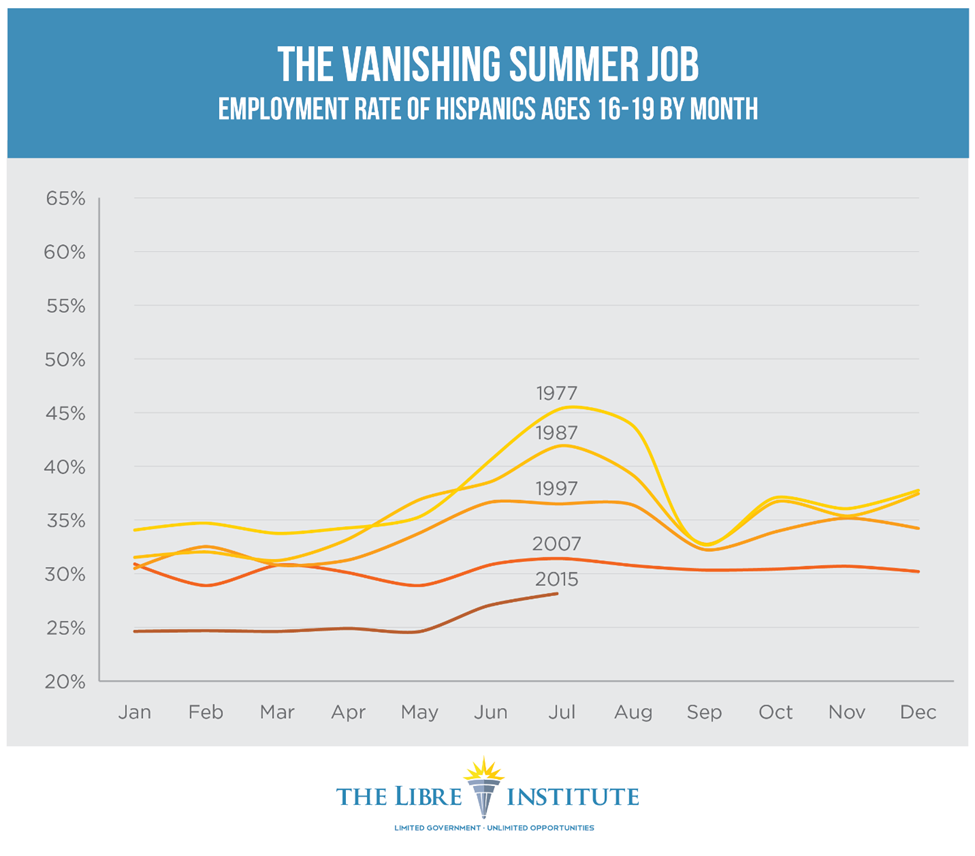

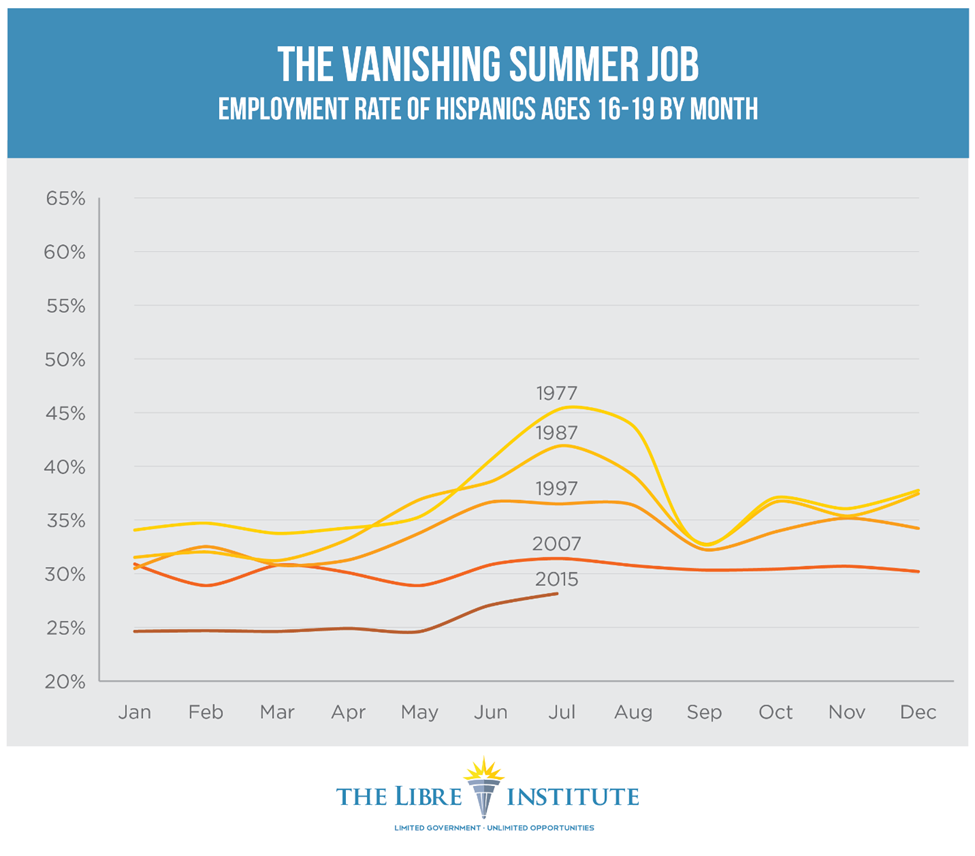

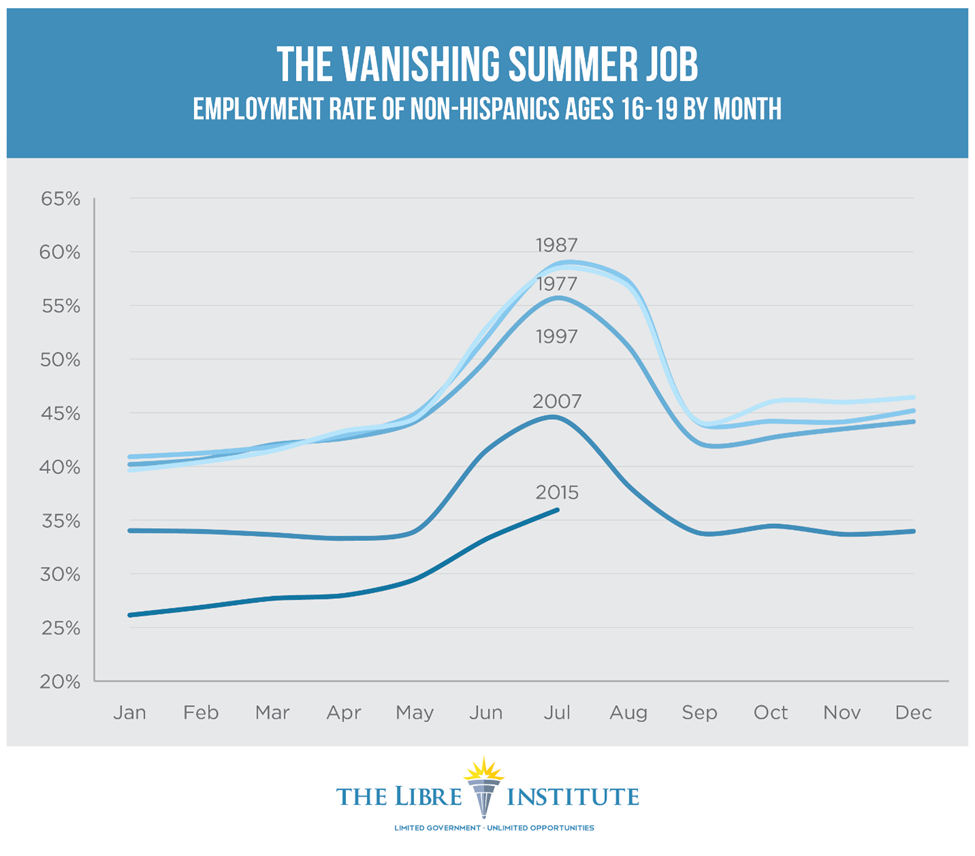

Since the late 1970’s, the familiar American teenage pastime of working a summer job between school years has been vanishing at an alarming rate. What was once an easy and common way for young Americans to gain work experience and earn a little spending money for summer vacation is now out of reach for many. While the decline in summer employment of young people has affected all groups in American society, the nation’s Hispanic population has been among the hardest hit. In two new graphs from The LIBRE Institute, based on similar graphs from Pew Research, the monthly employment rate of Hispanics and non-Hispanics 16-19 years of age is examined over the past four decades. Using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, seasonal fluctuations in employment rates are compared with different decades, and a striking pattern emerges.

At the beginning of every summer, around the month of May, teenage employment rises to a peak, and then falls in time for the start of school in September. Beginning in 1977, the lines go down steadily with every passing decade; starting, peaking, and ending lower on the y-axis than the decade before. The opportunities for American teenagers to seek summer employment are becoming scarcer, and the problem appears to be worsening.

However, this is not the only pattern to emerge. When we examine the same years using data for Hispanic teenagers rather than non-Hispanic, a second feature of the trend comes into focus. Not only have year-round teenage employment rates fallen every decade since the 1970’s, but the summer peaks for Hispanics are becoming flatter and flatter as time goes on. In 2007, a summer peak is barely visible at all. So far in 2015, the line is even flatter. Even though summer jobs are becoming rarer for all groups, the data indicates that Hispanics are disproportionately affected. Analysts worry about the impact that the future lack of summer jobs will have on our nation’s youth, but for Hispanic teenagers, that future is already here.

As noted by Pew Research, the decline in summer jobs can be connected to several possible explanations. There are “fewer low skill, entry level jobs than in the past, more schools restarting before Labor Day, more students enrolled in high school or college over the summer, more teens doing unpaid community service work as part of their graduation requirements or to burnish their college applications, and more students taking unpaid internships.” However, these trends have not taken place in a vacuum. Predictable, inevitable, and natural laws of economics have served to change the teen summer employment landscape as a result of bad policy. If policymakers wish to arrest this decline and restore job opportunities for coming generations, it is important to understand the effects of the policies that have landed us in the present predicament.

According to Mark Perry of the American Enterprise Institute, one of the policies that has had the biggest impact on teen unemployment and summer job opportunities is the minimum wage.

“Despite the wishful thinking of politicians like President Obama, the laws of supply and demand are not optional,” writes Perry, for AEIdeas. “The recent history of raising the minimum wage demonstrates its disproportionate negative effect on the least skilled, least experienced and least educated workers – teenagers.”

According to classical liberal economics, this is to be expected. Labor is a good like any other, and is sold by employees to employers for a price. As with any other good, when the price of labor increases, demand for labor decreases. When it becomes cheaper, employers buy more of it, but when it becomes more expensive, employers cannot afford to keep paying for it. This decline in the ability of employers to hire employees when the cost of doing so increases is one of the primary mechanisms by which rising minimum wages reduce job opportunities. Inability to pay is not often up to the employer, but is necessitated by circumstances. Rather than raise living standards for the many, these policies benefit only a select few. In return, opportunity is limited for everyone else. This is not a matter of opinion. It’s math.

This tradeoff between raising the minimum wage and raising unemployment is just as well understood in American households as it is in economics departments. No matter how many Americans support raising the minimum wage as an abstract idea or aspiration, a majority oppose it once the likely costs are taken into consideration. For U.S. Hispanics, the reversal is stark. According to a 2014 poll by Reason, when Hispanics are asked if they would support or oppose raising the minimum wage if they knew businesses would be forced to cut jobs, a full 58% say they would oppose it; more than double the number that opposed it originally.

Over the last few decades, the slow death and disappearance of the summer job, once an American icon, has given us a glimpse into the future. Hispanics are not among the select few who benefit from the policy, but have instead faced the worst of its consequences. Opportunities which still exist for many in other groups have now all but vanished for Hispanics. This is not a gloomy prediction, but a present and sobering reality.